When you write Go, a lot happens behind the scenes. Goroutines are lightweight, channels just work, memory is managed for you, and you never think about thread pools. All of that is powered by the Go runtime—a sophisticated piece of infrastructure that gets compiled into every Go binary.

This is the first article in a series where we’ll explore the Go runtime from the inside. We’ll look at how the scheduler multiplexes goroutines onto OS threads, how the memory allocator achieves lock-free fast-path allocations, how the garbage collector runs concurrently while reducing stop-the-world pauses to the bare minimum, and how the system monitor keeps everything running smoothly. Each of those will get its own deep-dive article.

But before any of that machinery can do its job, it has to be set up. That’s what the bootstrap is—the process that runs between the OS starting your binary and your func main() getting control. And that’s what we’re exploring today.

Let’s start with a question: how fast is Go at doing nothing?

Here’s a C program that does absolutely nothing:

int main() {

return 0;

}

And here’s the Go equivalent:

package main

func main() {

}

Let’s compile both and compare:

$ gcc -o nothing_c nothing.c

$ go build -o nothing_go nothing.go

$ ls -lh nothing_c nothing_go

-rwxrwxr-x 1 user user 16K Feb 7 12:05 nothing_c

-rwxrwxr-x 1 user user 1.5M Feb 7 12:05 nothing_go

$ time ./nothing_c

real 0m0.001s

$ time ./nothing_go

real 0m0.002s

The Go binary is almost 100x larger and takes roughly twice as long to run. And we’re doing nothing. What’s going on?

The answer is that Go is doing a lot before your main function runs. That 1.5MB of extra binary contains the entire runtime: a memory allocator, a garbage collector, a scheduler, a system monitor, and all the machinery needed to support goroutines, channels, and maps. Before you get control, Go has to set all of that up.

Let’s walk through the entire bootstrap process—everything that happens between the OS starting your binary and your func main() finally running.

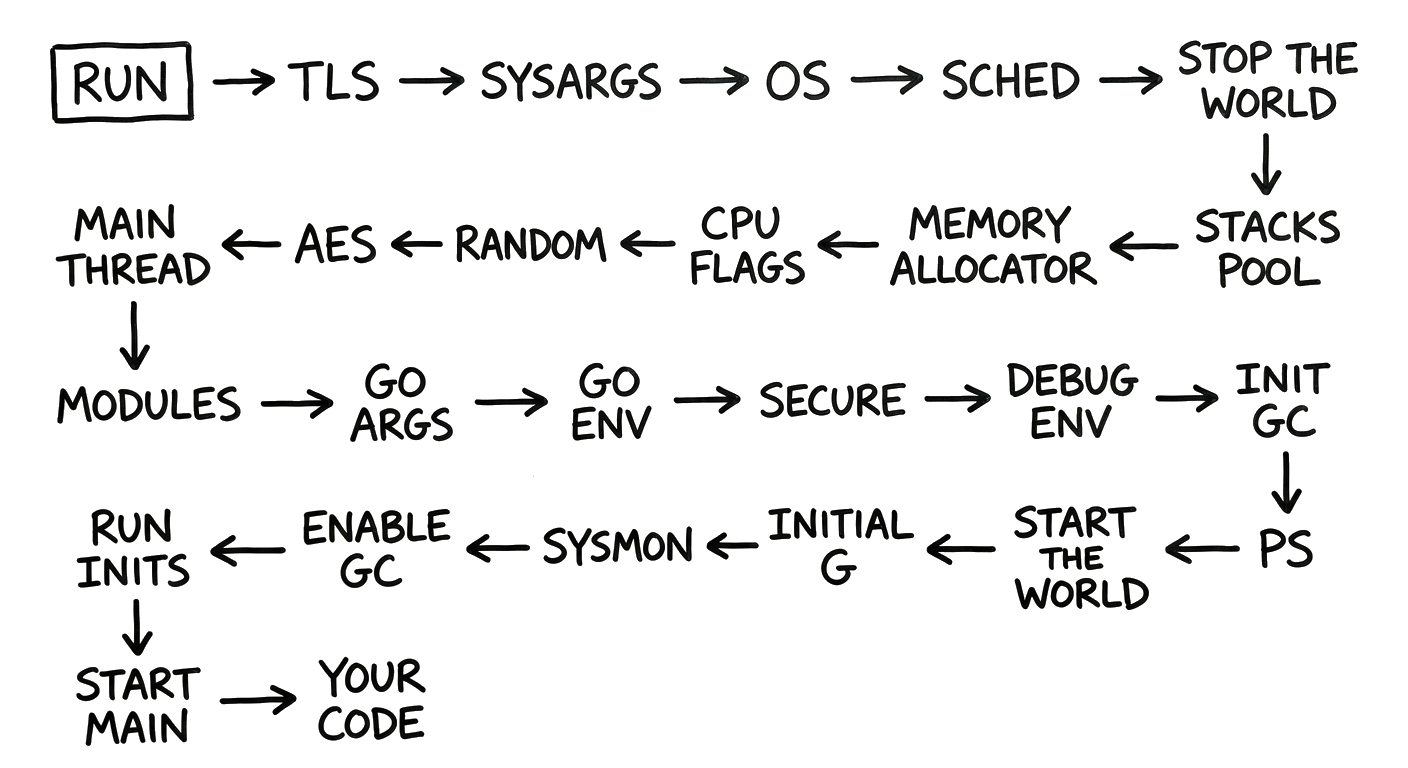

Here’s the big picture—every step the runtime takes before your code runs:

We’ll go through each of these steps in order. Keep this map in mind as we dive in—it helps to know where we are in the process.

So let’s start at the very beginning—what actually runs when you execute a Go binary?

The Entry Point: Not Your main()

The first surprise: your main function is not the entry point. We can prove this. Let’s use readelf to find the actual entry point of our do-nothing binary:

$ readelf -h nothing_go | grep "Entry point"

Entry point address: 0x467280

That’s a raw address. What function lives there? go tool nm maps addresses to symbol names:

$ go tool nm nothing_go | grep 467280

467280 T _rt0_amd64_linux

There it is—_rt0_amd64_linux, not main.main. The actual entry point is an assembly function inside the runtime (in src/runtime/rt0_linux_amd64.s

). There are equivalent entry points for every architecture Go supports: _rt0_arm64_linux, _rt0_386_linux, and so on. All they do is grab the command-line arguments from the stack and jump to rt0_go (in src/runtime/asm_amd64.s

), which is where the real bootstrap begins. It’s a big assembly function that lays the groundwork before any Go code can run. Here’s what it does, roughly in order:

First, it creates two things that Go needs from the very start: g0 and m0. Think of it this way—Go runs your code on goroutines, and goroutines run on OS threads. So before anything else can happen, the runtime needs at least one of each. That’s what g0 and m0 are: the first goroutine and the first thread. g0 is a bit special though—it won’t run your code. It’s reserved for the runtime’s own housekeeping, like scheduling other goroutines.

Then it sets up Thread-Local Storage (TLS). TLS is an OS-level mechanism that gives each thread its own private storage area—different threads can read the same TLS slot and get different values. Go uses it to store a pointer to the goroutine currently running on each thread, so the runtime can always answer the question “which goroutine am I right now?” quickly and without locks. This is so critical that the runtime immediately tests it by writing a magic value and reading it back—if TLS doesn’t work, the program aborts on the spot.

It also checks what kind of CPU it’s running on—what vendor it is, and what features it supports. Go binaries can be compiled to take advantage of newer CPU instructions for better performance, so the runtime verifies that the CPU actually has those features. If it doesn’t, the binary prints an error and exits rather than crashing with an illegal instruction later.

If the binary was built with CGO support, there’s an extra step to initialize the C runtime before proceeding.

With all the assembly-level groundwork done—TLS working, CPU features known, g0 and m0 linked—rt0_go transitions into Go code with four function calls: check() verifies compiler assumptions are correct, args() saves the command-line arguments, osinit() detects the number of CPUs (which becomes the default GOMAXPROCS), and finally schedinit()—where the real work happens.

Scheduler Initialization (schedinit)

Now comes the big one. schedinit() (in src/runtime/proc.go

) is the main initialization function that sets up all the critical runtime subsystems. Let’s walk through what it does in order.

Stop the World

The first thing schedinit() does is mark the world as stopped. “Stop the world” is a term you’ll hear a lot in Go runtime discussions—it means pausing all goroutines so the runtime can safely do work that requires nothing else to be running at the same time. In this case, no goroutines exist yet, so the world is already stopped by definition. But the runtime marks it explicitly, because several subsystems behave differently depending on whether goroutines might be running concurrently.

Think of it like setting up a restaurant before opening: you arrange the tables, prepare the kitchen, stock the ingredients—all before the first customer walks in. So what needs to be set up?

Stack Pool Initialization

Well, goroutines need stacks to run on. Go goroutines start with tiny 2KB stacks that grow dynamically, and the runtime keeps pools of pre-allocated stack segments organized by size so that creating a new goroutine is fast. stackinit() sets up these pools.

When a goroutine finishes and its stack is freed, it goes back into the pool for reuse rather than being returned to the OS. This is critical for performance—goroutine creation needs to be cheap, and asking the OS for memory on every go statement would be far too slow.

But stacks are just one kind of memory that goroutines use. They also need heap memory—for anything that escapes the stack, like slices, maps, or values returned by pointer.

Memory Allocator Initialization

That’s what mallocinit() takes care of. It sets up Go’s memory allocator, and the core idea is pretty intuitive: instead of asking the OS for memory every time your code does a make([]byte, 100), Go grabs large chunks of memory upfront and then hands out small pieces from those chunks. Much faster.

The allocator organizes memory by size classes—there are 68 of them, ranging from 8 bytes to 32KB. When you allocate a 50-byte object, Go doesn’t give you exactly 50 bytes. It rounds up to the nearest size class (64 bytes in this case) and gives you a slot from a pre-divided block of 64-byte slots. This keeps things simple and avoids fragmentation. For anything larger than 32KB, the allocator skips the size classes entirely and allocates directly from the heap.

The really clever part comes later, when Ps are created. Each P gets its own local memory cache, so most allocations don’t need any locks at all—a goroutine just grabs memory from its own P’s cache. Only when that cache runs empty does it need to go to the shared central lists for a refill. This is a big reason why Go can allocate memory so fast even with many goroutines running concurrently.

With the two biggest pieces in place—stacks and heap memory—the runtime moves on to a few smaller but important details.

CPU Flags and Hash Initialization

cpuinit() does a more detailed check of CPU capabilities beyond what the assembly code already detected—figuring out exactly which instruction set extensions are available.

Then alginit() picks the hash function that Go maps will use. If the CPU supports hardware AES instructions, Go uses them for hashing—it’s significantly faster. Otherwise, it falls back to a software implementation. This choice affects every map operation in your program, so it’s worth getting right early.

Now that the runtime knows what the hardware can do, it’s time to set up the software infrastructure that sits on top of it.

Modules, Types, and the Main Thread

This is where the runtime builds the internal tables that make Go’s type system work. modulesinit() builds the tables of all compiled packages—each containing type information, function metadata, and GC bitmaps. typelinksinit() and itabsinit() set up the interface dispatch tables that make Go’s interfaces work. And mcommoninit() finishes setting up m0 (our main thread) and registers it in the global list of all threads.

With the internal plumbing in place, the runtime can finally start looking outward—at the inputs your program received from the outside world.

Args, Environment, and Security

goargs() converts the raw C-style argv into the Go string slice that will become os.Args. goenvs() does the same for environment variables. Then secure() performs security checks, and checkfds() makes sure that stdin, stdout, and stderr are actually open—preventing a class of security issues that can arise with closed standard file descriptors.

One of those environment variables deserves special attention.

Debug Environment

The GODEBUG variable controls all sorts of runtime behaviors. A few handy ones:

GODEBUG=inittrace=1— prints timing for each package init functionGODEBUG=schedtrace=1000— prints scheduler state every secondGODEBUG=gctrace=1— prints GC events

These get parsed and applied here so they take effect for the rest of the bootstrap.

At this point, all the supporting pieces are in place. The runtime now turns to the two big remaining subsystems.

Garbage Collector Initialization

gcinit() prepares Go’s garbage collector—the system that automatically frees memory your program no longer needs. Go uses a concurrent mark-and-sweep GC, which means it does most of its work while your program keeps running, rather than stopping everything.

During initialization, the runtime sets up the machinery the GC will need later: the pacer, which decides when to trigger a collection (by default, when the heap has doubled in size); the sweeper, which reclaims unused memory after a collection; and the per-P work queues that GC workers will use to track which objects are still alive.

But here’s an important detail: the GC is initialized but not yet enabled. It won’t actually start running until gcenable() is called later in runtime.main(). Why? Because enabling the GC involves spawning goroutines (for background sweeping and memory scavenging) and creating channels—and none of that works until the scheduler and the rest of the runtime are fully set up. On top of that, triggering a GC cycle before type metadata and pointer maps are ready could cause the collector to scan incomplete data structures.

With the GC structures ready, there’s one last piece of the puzzle.

Processor (P) Initialization

The runtime needs to create the P (Processor) structures. Think of a P as a work station: a goroutine needs to sit at one to get any work done, and an OS thread is the worker that operates it. Each P comes with its own queue of goroutines waiting to run, its own memory cache (so allocations are fast and don’t need locks), and its own timers and GC worker state.

The number of Ps is determined by GOMAXPROCS, which defaults to the number of CPU cores detected earlier. So on an 8-core machine, you get 8 Ps—meaning up to 8 goroutines can run truly in parallel at any given moment.

Start the World

And with that, schedinit() calls worldStarted(). The “world” is now considered started—all the infrastructure is in place for goroutines to run concurrently. The restaurant is open for business.

With the scheduler, allocator, GC, and all the supporting infrastructure in place, the runtime is finally ready to create its first real goroutine.

Creating the Main Goroutine

Think of everything up to this point as building a car—we’ve assembled the engine (scheduler), the fuel system (memory allocator), and the exhaust (GC). Now it’s time to turn the key.

Back in rt0_go, after schedinit() returns, the runtime creates its first goroutine. But notice—this goroutine doesn’t run your main.main. It runs runtime.main, which is the runtime’s own main function. Your code comes later.

This goroutine gets a 2KB initial stack (from the stack pools we set up earlier) and is placed in the first P’s run queue, ready to go. Then the runtime kicks off the scheduling loop on m0—that’s the key turning. The scheduler immediately picks up the goroutine and starts executing runtime.main().

The engine is running. We’re almost at your code—but not quite yet.

runtime.main: The Last Mile

We’re finally in Go code running as a proper goroutine. But there’s still work to do before your code runs. Here’s runtime.main() (in src/runtime/proc.go

):

Max Stack Size and System Monitor

First, runtime.main() sets a limit on how big any goroutine’s stack can grow—1GB on 64-bit systems. If a goroutine blows past that (usually from infinite recursion), the program panics with a stack overflow.

Then it starts the system monitor (sysmon)—a dedicated background thread that acts as the runtime’s watchdog. It runs independently from the scheduler, keeping an eye on things: if a goroutine has been hogging a P for too long, sysmon forces it to yield. If an OS thread has been stuck in a system call, sysmon takes its P away and gives it to another thread so other goroutines can keep running. It also nudges the GC if it hasn’t run in a while, checks for network I/O that’s ready, and returns unused memory to the OS.

The main goroutine also gets locked to the main OS thread at this point. This is needed for compatibility with certain C libraries and GUI frameworks that expect specific operations to always happen on the “main” thread.

With the watchdog running and the main thread secured, the runtime can now start running your code—well, almost. There are still a few things left.

Runtime init() Functions

First, the runtime runs its own internal init() functions—the ones belonging to the runtime package and its dependencies. These finish setting up internal data structures that weren’t fully ready during schedinit().

With the runtime’s own initialization complete, the scheduler is fully operational, type metadata is in place, and channels work. That means it’s finally safe to turn on the GC.

Enabling the Garbage Collector

Remember how we said the GC was initialized but not enabled? This is where it finally gets switched on. gcenable() spawns the background sweeper and scavenger goroutines, and from this point on, the GC runs in the background, collecting unused memory whenever the heap grows large enough.

Why enable it now and not later? Because the next step—running your package init functions—can allocate lots of memory. The GC needs to be active by then.

Running Package init() Functions

Now comes something you’re probably familiar with: init() functions. The runtime walks through every package in your program and runs their init() functions in dependency order—if your package imports fmt, then fmt (and everything fmt depends on) gets initialized before your package does.

This is also when package-level variables get initialized. So if you have something like var db = connectToDB() at the top of a file, that runs now, during bootstrap—not when main() starts.

And now, finally, there’s nothing left between the runtime and your code.

Finally: Your main()

After all that—assembly entry point, TLS, CPU detection, memory allocator, scheduler, GC, system monitor, init functions—the runtime finally calls your main function.

But what happens when it returns?

After main() Returns

When your main returns, the runtime doesn’t immediately exit. It gives a brief grace period for any goroutines that are in the middle of handling panics to finish their deferred cleanup. But any other goroutines that are still running? They’re simply killed—no warning, no cleanup. If you need them to finish, you have to synchronize explicitly (for example, with a sync.WaitGroup).

Wrap Up

So, back to the question we started with: why is Go “slow” at doing nothing? Now you know—it’s not doing nothing at all. By the time your main function runs, the runtime has already built an entire execution environment from scratch: a first goroutine and thread, thread-local storage, stack pools, a memory allocator, hash functions for maps, a garbage collector, a scheduler with one P per CPU core, a system monitor thread, and all your package init functions.

That’s a lot of machinery. But it’s also what makes Go feel so effortless when you write it—goroutines are cheap because the stack pools and allocator are already there, memory management is invisible because the GC is already running, and concurrency just works because the scheduler was set up before your first line of code.

We’ve covered the bootstrap at a high level in this article, touching many pieces without going too deep into any of them. In the upcoming articles in this series, we’ll change that. We’ll take a close look at the Scheduler and how it juggles goroutines across threads, the Memory Allocator and why most allocations don’t need locks, and the Garbage Collector and how it cleans up memory while keeping stop-the-world pauses as short as possible. See you there!