In the previous post

, we watched the compiler transform optimized SSA into machine code bytes and package them into object files. Each .o file contains the compiled code for one package—complete with machine instructions, symbol definitions, and relocations marking addresses that need fixing.

But your program isn’t just one package. Even a simple “hello world” imports fmt, which imports io, os, reflect, and dozens of other packages. Each package is compiled separately into its own object file. None of these files can run on their own.

This is where the linker comes in. The linker’s job is to take all these separate object files and combine them into a single executable that your operating system can run.

Let me show you what the linker does and how it does it.

What the Linker Does

At a high level, the linker performs four main tasks:

1. Symbol Resolution: Your code calls fmt.Println, but that function is defined in a different object file. The linker finds all these cross-file references and connects them.

2. Relocation: Remember those placeholder addresses in the machine code? The linker patches them with actual addresses now that it knows where everything will live in memory.

3. Dead Code Elimination: If you import a package but only use one function, the linker removes all the unused functions. This keeps your binary small.

4. Layout and Executable Generation: The linker decides where in memory each piece of code and data will live, then writes out an executable in the format your OS expects (ELF on Linux, Mach-O on macOS, PE on Windows).

Let’s walk through each of these steps, starting with how the linker figures out what symbols exist and where they live.

Symbol Resolution

Every object file contains symbols—names that identify functions, global variables, and other program elements. Some symbols are defined in a file (the actual code or data lives there), while others are just referenced (the code uses them, but they live somewhere else).

Let me show you what I mean:

// main.go

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

fmt.Println("Hello")

}

When compiled, your main.o contains main.main—that’s your function, complete with machine code. But it also references fmt.Println, and that code isn’t here. It’s just a name pointing somewhere else.

Note: In practice,

fmt.Printlngets inlined by the compiler, so there’s no actual cross-package reference in this case. But the concept holds for functions that don’t get inlined.

Over in fmt.o, you’ll find the actual fmt.Println implementation. But that file references io.Writer, os.Stdout, and dozens more symbols from other packages.

Each package defines some symbols and references others. The linker needs to match all these references with their definitions. To do that, it first needs to build a complete picture of what exists.

The Loader: Building a Global Symbol Index

Before the linker can do anything useful, it needs to know about every symbol in your program. That’s the job of the Loader (src/cmd/link/internal/loader/

).

The Loader reads object files and builds a unified index of all symbols. It starts with your main package, reads that object file, and discovers its imports. Your code uses fmt, so now fmt needs to be loaded. And fmt imports io, os, reflect, and others. The Loader keeps following imports until it has found every package your program depends on. The runtime package always gets loaded too, since every Go program needs it.

As it reads each file, the Loader records every symbol and connects references to definitions. When your code calls a function from another package, the object file just says “I need this symbol.” The Loader looks it up and records where it points. Most symbols are identified by name, but some—like string literals—are content-addressable, identified by a hash of their contents. If two packages both use "Hello", they produce the same hash and share a single copy in the final binary.

The index itself is straightforward. Each symbol gets a unique integer ID. The Loader maintains a few key data structures: a mapping from symbol ID to its location (which object file, which local index within that file), lookup tables to go from a name like fmt.Println to its ID, and space for attributes like “is this symbol reachable?” that get filled in later. The actual code and data bytes stay in the object files—the Loader just records where to find them.

By the end, the Loader has a complete picture: every symbol indexed, every reference resolved. You can find the loading logic in src/cmd/link/internal/loader/loader.go

.

But having everything indexed doesn’t mean we need everything. Time to trim the fat.

Dead Code Elimination

The Loader indexed every symbol from every package, but you probably don’t use all of them. If you import fmt just to call Println, you don’t need the dozens of other functions in that package.

The linker solves this with dead code elimination. Starting from main.main, it traces through every function call and every global variable access, setting that “is this symbol reachable?” attribute we mentioned earlier. When it’s done, anything not marked gets dropped. If you imported a package with fifty functions but only called one, the other forty-nine disappear.

This is why Go binaries stay reasonably small despite static linking. You can find this logic in src/cmd/link/internal/ld/deadcode.go

.

With symbols resolved and dead code eliminated, the linker knows exactly what needs to go into the final binary. But there’s a problem: the machine code still has placeholder addresses for symbols that live in other packages.

Relocation

When the compiler generated machine code for a package, it knew about symbols within that package but not about symbols defined elsewhere. Every call to a function in another package, every reference to a variable from an imported module—those are just placeholders saying “fill this in later.” The linker’s job now is to figure out where all these cross-package symbols actually go, and then patch those placeholders with real addresses.

This creates a chicken-and-egg situation: you can’t fill in the addresses until you know where everything is, but you need to lay out all the code and data first to know where everything is. The linker solves this in two passes: first assign addresses to everything, then go back and patch the code.

Address Assignment

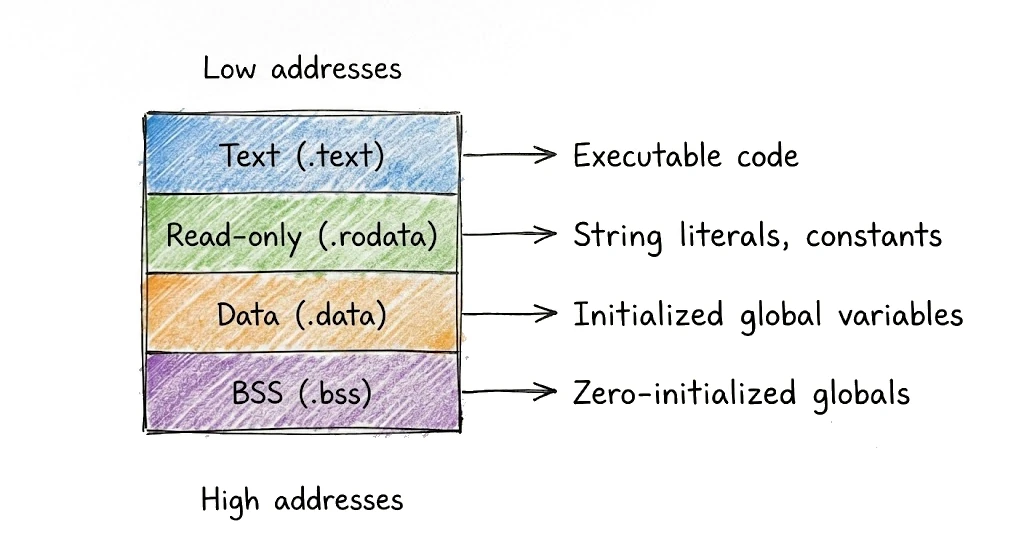

The linker organizes memory into sections based on what each symbol contains and how it will be used:

The linker processes symbols one by one, placing each at the next available address in its section. Functions get aligned to appropriate boundaries (typically 16 or 32 bytes depending on the architecture) for cache efficiency. Read-only data gets grouped together so it can be protected from modification. The .bss section is special—it takes no space in the file since everything there is just zeros, but the OS allocates the memory when the program loads. By the end of this pass, every symbol has a concrete address.

Now that everything has an address, it’s time to fix up all those placeholders.

Patching Relocations

Each placeholder has an associated relocation record saying what symbol’s address belongs there. The linker goes through every relocation, looks up the target’s address, and patches it in. For function calls, the CPU expects a relative offset (“jump forward 500 bytes”), so the linker computes the distance between the call site and the target. For global variable references, it writes the absolute address directly. When this pass finishes, the machine code is complete—every placeholder replaced with a real address.

The linker now has fully-linked machine code. All that’s left is packaging it into a file the operating system can actually run.

Generating the Executable

Finally, the linker organizes everything into sections, groups them into segments, and writes the executable file. Let’s look at how this organization works.

Sections

The linker groups symbols into sections based on what they are and how they’ll be used:

.textholds executable code—your functions, marked read-execute.rodataholds read-only data—string literals, constants, type descriptors.dataholds initialized global variables—read-write.bssholds zero-initialized globals—read-write, but takes no space in the file.noptrdataand.noptrbsshold data the garbage collector can ignore (no pointers)

Go also generates special sections for runtime metadata. The .gopclntab section contains the PC-line table—the mapping from program counter values to source file and line numbers that makes stack traces work and enables reflection.

But sections are the linker’s internal organization. The operating system thinks in terms of segments.

Segments

Sections get grouped into segments for loading. While sections are the linker’s view of the data, segments are the OS loader’s view. The OS doesn’t care about individual sections; it maps entire segments into memory with the right permissions.

A typical Go executable has a text segment (code + read-only data, mapped read-execute) and a data segment (writable data + BSS, mapped read-write). On some platforms there’s also a separate read-only data segment between them for .rodata.

The segment layout matters for security. Modern systems use W^X (write xor execute)—memory can be writable or executable, but not both. By separating code and data into different segments with different permissions, the linker enables this protection.

With segments defined, the linker writes everything to disk in a format the OS understands.

File Format and Loading

Different operating systems use different executable formats—Linux uses ELF, macOS uses Mach-O, Windows uses PE. Despite the differences, they all contain:

- A header identifying the file format and architecture

- Program headers (or equivalent) describing segments to load

- Section headers describing the contents for debuggers and tools

- The actual code and data bytes

- Optionally, debug information (DWARF format)

One interesting detail: the header specifies an entry point—where the OS starts executing—and it’s not your main function. It’s Go runtime startup code like _rt0_amd64_linux, which sets up the stack, initializes the memory allocator, starts the garbage collector, and launches the scheduler before finally calling your main.main.

You can find the output code in src/cmd/link/internal/ld/elf.go

and similar files for other formats. If you want to explore the final structure of a Go binary in more detail, check out my talk Deep dive into a Go binary

from GopherCon UK.

Everything we’ve discussed so far assumes the default case: a standalone executable with everything bundled in. But the linker can produce other kinds of output too.

Static Linking, Dynamic Linking, and Build Modes

Go prefers static linking—bundling everything into one self-contained binary. The Go runtime, the standard library, all your dependencies: they’re all compiled in. No external dependencies means you can copy the binary to another machine and it just works.

When you use cgo, Go has to dynamically link against system libraries like libc. The linker adds a .dynamic section with symbol tables, library names, and relocation entries. It also specifies an interpreter—the path to the dynamic linker (/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 on Linux). When you run the program, the kernel loads the dynamic linker first, which resolves external symbols and loads shared libraries before jumping to your code.

With -buildmode flags, the linker can produce other output types: C-compatible static libraries (c-archive), shared libraries (c-shared), or Go plugins (plugin). Each mode changes what gets exported, how the runtime initializes, and what file format gets written.

Now that we’ve seen all the pieces, let’s watch them work together on a concrete example.

Walking Through a Complete Example

Let’s trace a simple program with two packages through the entire linking process.

main.go:

package main

import "example/greeter"

func main() {

greeter.Hello()

}

greeter/greeter.go:

package greeter

import "fmt"

//go:noinline

func Hello() {

fmt.Println("Hello")

}

Note: The

//go:noinlinedirective prevents the compiler from inliningHellointomain.main. Without it, the compiler would inline the function and there would be no cross-package call for the linker to resolve.

Let’s follow this program through each phase of linking.

After Compilation

The compiler produces separate object files. main.o contains main.main and has a reference to example/greeter.Hello—it calls that function but doesn’t have the code. There’s a relocation marking where the call address needs to be filled in.

greeter.o contains example/greeter.Hello, which in turn references fmt.Fprintln (that’s what fmt.Println calls internally). And fmt.a (the archive for the fmt package) has the actual implementation, along with references to io.Writer, os.Stdout, and more.

The linker starts by loading all these pieces and figuring out what’s what.

Loading and Resolving

The linker loads all these files and builds a symbol table. Note that symbol names include the full module path:

Symbol Table:

main.main → defined in main.o

example/greeter.Hello → defined in greeter.o

fmt.Fprintln → defined in fmt.a

(plus hundreds more from runtime and std library)

Every reference can be matched to a definition. If something were missing, the linker would stop here with an undefined symbol error.

Next, the linker figures out what’s actually used.

Dead Code Elimination

Starting from main.main, the linker traces through all the calls:

main.main → calls example/greeter.Hello

example/greeter.Hello → calls fmt.Fprintln

fmt.Fprintln → calls io.Writer methods, uses os.Stdout

...

Everything in this chain is marked reachable. Anything not in the chain—functions from packages you imported but never actually used—gets dropped.

With the set of reachable symbols determined, the linker assigns each one an address.

Assigning Addresses

Now the linker lays out all the reachable symbols in memory. Here’s what it looks like for our example (addresses from an actual build):

Text section (starting at 0x401000):

0x46f1e0: _rt0_amd64_linux (entry point)

0x439040: runtime.main

0x491b20: main.main

0x491ac0: example/greeter.Hello

0x48cac0: fmt.Fprintln

...

Data section (starting at 0x554000):

0x55e148: os.Stdout

...

Now the linker can patch all the placeholder addresses in the machine code.

Patching Relocations

With addresses assigned, the linker goes back and fills in all the placeholders.

In main.main, there’s a call to example/greeter.Hello. We can see it in the disassembly:

TEXT main.main(SB)

0x491b20 CMPQ SP, 0x10(R14)

0x491b24 JBE 0x491b31

0x491b26 PUSHQ BP

0x491b27 MOVQ SP, BP

0x491b2a CALL example/greeter.Hello(SB) ← patched with offset to 0x491ac0

0x491b2f POPQ BP

0x491b30 RET

The CALL instruction at 0x491b2a contains a relative offset that jumps to example/greeter.Hello at 0x491ac0. Same thing for the call from greeter.Hello to fmt.Fprintln—the linker computes the offset and patches it in.

Now all the jumps and calls point to the right places.

All that’s left is writing the final file.

Writing the Executable

Finally, the linker writes everything out. On Linux, we can inspect the result with readelf (on macOS, use otool -h):

$ readelf -h ./example

ELF Header:

Magic: 7f 45 4c 46 02 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

Class: ELF64

Data: 2's complement, little endian

Type: EXEC (Executable file)

Machine: Advanced Micro Devices X86-64

Entry point address: 0x46f1e0

Number of program headers: 6

Number of section headers: 25

...

There it is—a complete, standalone executable. The entry point 0x46f1e0 is _rt0_amd64_linux, the runtime startup code that will eventually call our main.main.

If you want to see this happening on your own code, there are some useful commands to explore.

Try It Yourself

If you want to peek behind the curtain, there are a few commands that let you see what the linker is doing.

To watch the linker work, pass -v through ldflags:

$ go build -ldflags="-v" .

# example

build mode: exe, symbol table: on, DWARF: on

HEADER = -H5 -T0x401000 -R0x1000

107437 symbols, 20441 reachable

48122 package symbols, 39987 hashed symbols, 14790 non-package symbols, 4538 external symbols

112153 liveness data

You’ll see how many symbols were loaded, how many are reachable after dead code elimination, and other build information.

Once you have a binary, you can inspect its symbol table with nm:

go tool nm ./example | less

This dumps every symbol in the executable along with its address. It’s a lot of output—even our simple program has over 2000 symbols from the runtime.

To see how the sections are laid out in memory, use your platform’s binary inspection tool:

readelf -S ./example # Linux

otool -l ./example # macOS

And if you want to see the entire build process, including the exact link command:

go clean && go build -x .

The go clean ensures you get the full output—without it, cached builds might skip steps.

This prints every command the go tool runs. You’ll see the compiler invocations, then the linker invocation with all its flags. It’s a good way to understand what’s happening under go build.

Let’s wrap up what we’ve learned.

Summary

The linker is the final step in the compilation process. It takes separate object files and combines them into a single executable:

Symbol Resolution: The Loader builds a global index of every symbol in your program, following imports recursively and connecting references to definitions. Content-addressable symbols let identical data (like string literals) be shared across packages.

Dead Code Elimination: Starting from

main.main, the linker traces reachability and drops everything that isn’t used. This is why Go binaries stay reasonably small despite static linking.Relocation: The linker assigns each symbol a concrete address, organizing them into sections (

.text,.rodata,.data,.bss), then patches all the placeholder addresses in the machine code.Executable Generation: Sections get grouped into segments with appropriate permissions (W^X), and the linker writes everything out in the OS-specific format (ELF, Mach-O, PE). The entry point isn’t your

main—it’s runtime startup code that initializes the Go runtime before calling your code.

Go’s linker also handles different build modes—from the default statically-linked executable to C archives, shared libraries, and plugins.

If you want to dive deeper into the linker, explore src/cmd/link/internal/ld/

. The code is well documented, and seeing how a real production linker works is fascinating.

And with that, we’ve completed our journey through the Go compiler! From source code through scanning, parsing, type checking, IR optimization, SSA transformation, code generation, and finally linking—your Go program is now a standalone executable ready to run.

But the story doesn’t end here. That executable contains the Go runtime: the scheduler that manages goroutines, the garbage collector that reclaims memory, the memory allocator, and all the machinery that makes Go’s concurrency model work. In the next series, we’ll explore how the runtime brings your program to life. Stay tuned!