Every time you save a document, download a photo, or install an application, you’re trusting a filesystem to keep your data safe. Think about it—filesystems are this invisible layer between your applications and raw storage hardware. They turn a sea of numbered blocks into the familiar world of files and folders that we all take for granted.

But what exactly does a filesystem do? And what makes it so tricky to get right? In this series, we’re going to explore filesystems like FAT32, ext4, Btrfs, and others. But before we get there, I want to build a solid foundation with you. We’ll start at the very bottom—how storage hardware actually works—and work our way up to the abstractions that filesystems provide.

By the end of this article, you’ll have a good grasp of the fundamental concepts that every filesystem has to deal with. Trust me, this will make the rest of the series much easier to follow.

So let’s begin where everything begins: with the raw storage hardware itself.

The Raw Material: Storage Hardware

What does a filesystem actually have to work with?

Sectors: The Smallest Unit

Whether you’re dealing with a spinning hard drive (HDD) or a solid-state drive (SSD), they all present themselves to the operating system the same way: as a linear array of sectors. A sector is simply the smallest unit the hardware can read or write.

Sectors are typically 512 bytes or 4096 bytes. The larger size tends to be more efficient for high-capacity drives—you get less overhead for error correction and addressing.

Now here’s the key insight, and it’s an important one: the drive doesn’t know what’s in these sectors. To the hardware, sector 0 and sector 1,000,000 look exactly the same—they’re just numbered slots holding bytes. The drive has absolutely no concept of “files” or “directories.” That’s entirely the filesystem’s job to figure out.

But before the filesystem gets involved, the operating system needs a way to talk to these drives.

How the Operating System Sees It

When you plug in a drive, the operating system sees it as a block device—basically a device that reads and writes fixed-size blocks. The OS can ask the drive to read a specific sector, write data to a range of sectors, or tell it how many sectors it has. And that’s pretty much it! The block device interface is beautifully simple:

// Conceptually, a block device provides:

size_t read_sectors(uint64_t start_sector, size_t count, void *buffer);

size_t write_sectors(uint64_t start_sector, size_t count, void *buffer);

uint64_t get_sector_count(void);

size_t get_sector_size(void); // Usually 512 or 4096

A 1TB drive with 512-byte sectors has about 2 billion sectors. A 1TB drive with 4KB sectors has about 250 million sectors. Either way, you’re looking at a giant array of numbered slots.

Now, this simple interface hides some interesting complexity happening inside the drive itself.

HDDs vs SSDs: Same Interface, Different Internals

Hard disk drives (HDDs) store data magnetically on spinning platters. A read/write head physically moves across the surface to access different sectors. Because of this mechanical movement, sequential access is fast—reading sectors 1000-2000 in order is no problem since the head barely moves. But random access is slow. Jumping from sector 1000 to sector 500,000 means physically moving the head across the platter, and that takes time.

Solid-state drives (SSDs) use flash memory with no moving parts. They can access any sector equally fast (well, mostly). But SSDs have their own quirks. They can’t just overwrite data directly—they have to erase first, then write. And erasure happens in large units called “erase blocks,” typically 128KB to 512KB. The SSD controller handles all this complexity internally through wear leveling and garbage collection, so you don’t have to think about it.

Here’s the neat part: despite these huge differences under the hood, both types of drives present the exact same block device interface to the operating system. The filesystem doesn’t need to know if it’s talking to spinning rust or flash memory—it just reads and writes sectors.

But before we can put a filesystem on this sea of sectors, we usually need to carve it up into manageable pieces.

Dividing the Disk: Partitions

A partition is simply a contiguous range of sectors that you decide to treat as an independent unit.

Why would you want to partition a drive? Well, maybe you want to run both Windows and Linux on the same physical drive—Windows using NTFS on one partition, Linux using ext4 on another. Or maybe you just want to keep your operating system separate from your data, so if you need to reinstall the OS, your files stay safe. Partitions also provide isolation: if one partition gets corrupted, the others remain untouched. And sometimes you just need different partitions for different purposes—a swap partition here, a boot partition there, a big data partition for everything else.

Of course, this raises a question: how does the system keep track of where each partition begins and ends?

The Partition Table

That’s where the partition table comes in. It’s a small data structure, usually right at the very beginning of the disk, that describes how the disk is divided up. There are two common formats you’ll encounter:

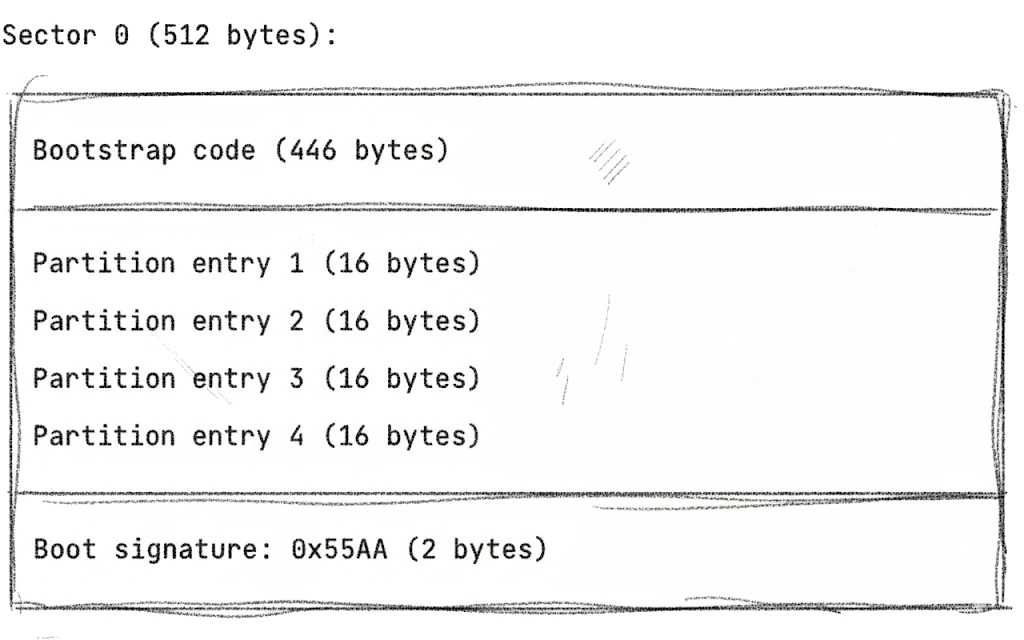

MBR (Master Boot Record) is the legacy format from 1983:

Let’s break this down. The bootstrap code takes up most of the space—446 bytes where you install your boot loader (GRUB, LILO, or similar) to start your operating system.

The four partition entries come next, 16 bytes each. Each entry tells you where the partition starts, how big it is in sectors, what type it is (0x07 for NTFS, 0x83 for Linux, and so on), and whether it’s bootable.

Finally, there’s the boot signature—the magic bytes 0x55AA that mark this as a valid MBR.

MBR works, but it has some frustrating limitations. You can only have 4 primary partitions (or 3 primary plus 1 extended partition with logical partitions inside—it gets messy). The maximum disk size is 2TB because of 32-bit sector addresses, which is a real problem with modern drives. And there’s no redundancy—if sector 0 gets corrupted, you lose the entire partition table.

GPT (GUID Partition Table) is the modern format that fixes these issues:

Sector 0: Protective MBR (for backward compatibility)

Sector 1: GPT Header

Sectors 2-33: Partition entries (128 entries × 128 bytes each)

...

Sectors N-33 to N-2: Backup partition entries

Sector N-1: Backup GPT header

The Protective MBR in sector 0 makes the disk look like it has one partition spanning the entire drive, so old MBR-only tools don’t accidentally overwrite your GPT data. The GPT Header contains the disk’s unique identifier, the location of the partition entries, and checksums for integrity verification.

GPT gives you up to 128 partitions by default—way more than you’ll probably ever need. It supports disks larger than 2TB thanks to 64-bit addresses. Each partition gets a unique GUID, which makes identification much more reliable. And here’s the really nice part: GPT stores a backup copy of the partition table at the end of the disk, plus CRC32 checksums to detect corruption. Much more robust than MBR.

When you create a partition, you’re essentially saying: “Sectors 2048 through 500,000,000 belong to partition 1.” The filesystem then gets to use those sectors however it wants.

So now we have a partition—a dedicated chunk of sectors. What happens next?

Inside a Partition

Once you have a partition, you format it with a filesystem. The filesystem takes ownership of those sectors and organizes them according to its own rules.

Here’s something interesting: from the filesystem’s perspective, it doesn’t care that it’s in a partition—it just sees a block device with a certain number of sectors. The filesystem writes its structures starting at sector 0 of the partition (which might actually be sector 2048 of the physical disk, but the filesystem doesn’t need to know that).

Now we’ve got our raw material sorted out—sectors organized into partitions. It’s time to see what a filesystem actually does with all of this.

What Filesystems Actually Do

Alright, so now we understand what a filesystem has to work with: a linear array of numbered sectors. But you and I don’t want to think about sectors—we want files and directories! The filesystem bridges this gap by providing several essential services.

1. Naming: From Numbers to Names

The most fundamental job of a filesystem is mapping names to data. Instead of saying “read sectors 50,000-50,007,” you get to say “read /home/alice/photo.jpg.” Much nicer, right?

To make this work, the filesystem needs a namespace (the hierarchical structure of directories and files), directory entries (data structures that map names to file metadata), and path resolution (the ability to walk the directory tree to find a file).

Let me walk you through what actually happens when you open /home/alice/photo.jpg. The filesystem starts by finding the root directory. Then it looks up “home” in the root directory to get its location. It reads the “home” directory and looks up “alice” to get that location. It reads the “alice” directory, looks up “photo.jpg,” gets the file’s metadata, and finally returns the file’s data location to the caller.

That’s a lot of steps! Each filesystem implements this dance differently, but they all solve the same fundamental problem: turning human-readable paths into sector addresses.

But naming is just the beginning. The filesystem also needs to figure out where to actually put all this data.

2. Space Allocation: Who Gets What?

When you create a new file or append to an existing one, the filesystem needs to find free space quickly.

This sounds simple enough, but think about the challenges for a moment. A 1TB disk has millions of allocation units—how do you search through all of that efficiently? Files grow and shrink all the time, creating fragmentation—how do you deal with that? Multiple processes might be writing simultaneously—how do you avoid conflicts?

Different filesystems tackle this in different ways. Some use bitmaps, where each bit represents one block (0 means free, 1 means used). It’s simple and elegant, but can be slow to scan through. Others use free lists—a linked list of free blocks. Fast to allocate from, but fragmentation becomes a real headache. More sophisticated filesystems use B-trees or similar structures for fast searching. They’re more complex to implement, but scale much better. And then there’s the FAT approach—a table where each entry points to the next block in a chain. We’ll see a lot more of that one later in this series.

So we can name files and allocate space for them. But there’s more to a file than just its content.

3. Metadata: More Than Just Content

How many bytes is this file? When was it created, modified, or last accessed? Who can read, write, or execute it? Which user owns it? Is it a regular file, a directory, a symlink, or something else entirely?

The filesystem has to store all this metadata somewhere and keep it synchronized with the actual file content. That’s trickier than it sounds! Unix-like filesystems use inodes (index nodes) for this. FAT filesystems store metadata in directory entries, though with pretty limited information. NTFS uses Master File Table records. Each approach has its own tradeoffs, which we’ll explore in detail when we get to those specific filesystems.

All of this—naming, allocation, metadata—works great when everything goes smoothly. But what happens when things go wrong?

4. Crash Recovery: When Things Go Wrong

Here’s a scary thought: what happens if the power fails while you’re in the middle of writing a file? The filesystem might be left in an inconsistent state—some blocks written, others not, metadata completely out of sync with the actual data.

Filesystems use various strategies to handle this nightmare scenario:

Journaling: Before making any changes, write a log of what you intend to do. If a crash happens, you can replay the journal to restore consistency. This is what ext4, NTFS, and XFS do, and it works really well.

Copy-on-write (CoW): Never modify data in place—always write to new locations. The old, consistent version remains perfectly valid until the new one is complete. This is how Btrfs and ZFS work, and it’s pretty clever.

fsck (filesystem check): Scan the entire filesystem looking for inconsistencies and try to fix them. This is painfully slow and was the primary recovery method before journaling came along. These days it’s mostly a fallback.

Without some form of crash recovery, a single power failure could corrupt your entire filesystem. That’s why modern filesystems invest so heavily in this area.

Now that we know what filesystems need to accomplish, let’s look at the actual building blocks they use to get the job done.

Common Concepts Across Filesystems

The details vary from one filesystem to another, but the underlying concepts are remarkably similar.

The Superblock / Boot Sector

Every filesystem needs a starting point—some fixed location where the OS can find basic information about the filesystem. This is typically called a superblock (that’s the Unix terminology) or boot sector (DOS/Windows terminology).

What’s in this structure? First, there’s usually a magic number—a special value that identifies the filesystem type. This is how the OS knows whether it’s looking at ext4 or NTFS or something else entirely. Then there’s geometry information: the block size, total number of blocks, how many are free. The superblock also tells you where to find the root directory, what optional features are enabled, and includes unique identifiers like UUIDs or volume labels.

// Conceptually, every filesystem has something like this:

struct superblock {

uint32_t magic; // Filesystem identifier

uint32_t block_size; // Bytes per block

uint64_t total_blocks; // Total blocks in filesystem

uint64_t free_blocks; // Available blocks

uint64_t root_location; // Where the root directory lives

// ... more fields

};

Because this structure is so critical, filesystems often store multiple copies at different disk locations. If one copy gets corrupted, you can recover from a backup. Smart, right?

The superblock tells us the basics, but there’s another fundamental concept we need to understand: how filesystems actually divide up the disk space.

Blocks: The Allocation Unit

While the hardware works in sectors (512 or 4096 bytes), filesystems typically work in larger blocks (also called clusters in FAT terminology). You’ll commonly see 1KB blocks in some smaller filesystems, 4KB blocks in most modern systems (it matches the x86 page size and modern sector size nicely), and occasionally 8KB to 64KB blocks for large files or specialized workloads.

Why not just use sectors directly? Well, think about a 1GB file. With 4KB blocks, you need 262,144 allocation entries to track it. With 512-byte sectors, you’d need 2,097,152 entries—that’s a lot more bookkeeping! Larger blocks also align nicely with memory pages, SSD erase blocks, and modern disk sectors. And powers of two make address calculations fast.

The tradeoff? Larger blocks waste space for small files. A 100-byte file sitting in a 4KB block wastes 3,996 bytes. Ouch. Some filesystems like ext4 try to mitigate this with techniques like inline data or tail packing, but it’s always a balancing act.

We’ve talked about blocks for storing file content, but what about all that metadata we mentioned earlier? That needs to live somewhere too.

File Metadata Structures

Every filesystem needs to store metadata about each file somewhere. There are two main approaches you’ll see.

Unix-like filesystems (ext4, XFS, Btrfs) use inodes, or index nodes. An inode contains all the metadata about a file except the filename—the file type and permissions, the owner and group, the size, timestamps, and pointers to the actual data blocks.

// Simplified inode structure

struct inode {

uint16_t mode; // Type + permissions

uint16_t uid; // Owner

uint32_t size; // File size

uint32_t atime; // Access time

uint32_t mtime; // Modification time

uint32_t ctime; // Change time (metadata)

uint32_t blocks[15]; // Pointers to data blocks

};

Wait, where’s the filename? It’s stored separately, in the parent directory. This might seem weird at first, but it enables something cool: hard links. Multiple directory entries can point to the same inode, so you get one file with many names.

FAT filesystems take a different approach: all metadata lives directly in the directory entry alongside the filename. This is simpler to understand, but it means you can’t have hard links or Unix-style permissions.

Speaking of directory entries, let’s look more closely at how directories themselves work.

Directories: The Namespace Structure

Here’s something that might surprise you: a directory (or folder) is really just a special kind of file. It contains a list of entries that map names to files—each entry has a filename and a reference to the file’s metadata (like an inode number or cluster number).

How directories are implemented varies quite a bit. FAT32 uses a simple linear list, which works fine but gets slow with large directories. Some filesystems use hash tables for fast lookups, like ext3’s htree. Others use B-trees, which stay sorted and efficient for all operations—that’s what Btrfs and XFS do.

The root directory is special—its location has to be known without looking anything else up. That’s why the superblock always contains a pointer to it.

There’s one more critical piece of bookkeeping every filesystem needs to handle: knowing which blocks are available and which are already taken.

Free Space Tracking

There are a few common approaches to solving this problem.

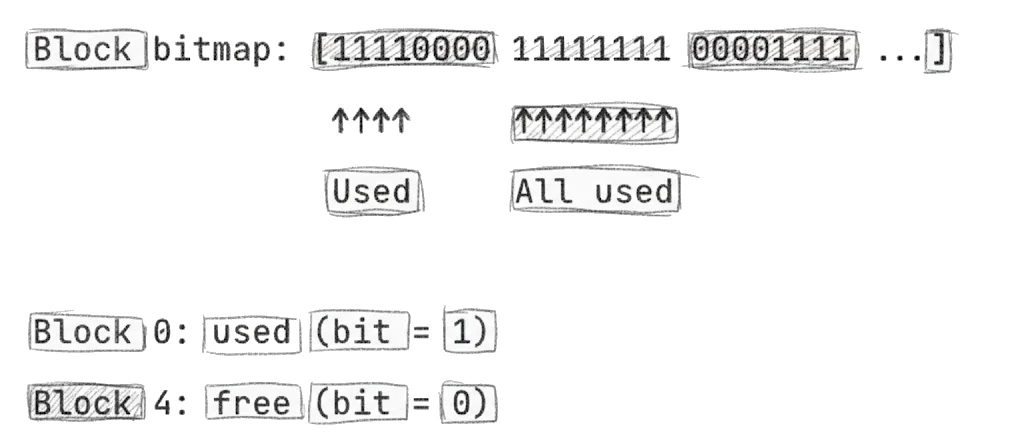

The simplest is a bitmap—an array where each bit represents one block:

Bitmaps are simple, compact, and make it easy to find contiguous free space. The downside is you have to scan the entire bitmap to count free blocks.

Another approach is a free block list—a linked list of free blocks. Allocation is O(1) since you just grab from the head of the list. But it’s hard to find contiguous space, and fragmentation becomes a real problem.

More sophisticated filesystems use a B-tree of free extents—a tree structure that tracks free ranges. This gives you fast allocation and makes it easy to find large contiguous regions, but it’s more complex to implement and there’s overhead for maintaining the tree.

Most modern filesystems actually combine these approaches—bitmaps for small-scale allocation decisions, with additional structures like ext4’s buddy allocator or XFS’s free space B-trees for efficiency. You pick the right tool for each job.

At this point, you might be wondering: if all filesystems need to solve the same problems, why are there so many different ones? The answer comes down to tradeoffs.

The Fundamental Tradeoffs

Every filesystem makes tradeoffs. There’s no perfect filesystem—just different ones optimized for different things. Understanding these tradeoffs helps you appreciate why so many different filesystems exist.

Simplicity vs Features

Consider FAT32. It’s dead simple—essentially just a linked list (the FAT) plus linear directory entries. It’s so easy to implement that every device on the planet supports it. But you give up permissions, journaling, large file support, and efficient large directory handling.

Btrfs is the opposite. It’s feature-rich with copy-on-write, snapshots, built-in RAID, compression, and checksums. But it’s complex, with multiple B-trees and sophisticated space management. When bugs happen, they’re harder to find and fix.

Simplicity versus features is just one axis. There’s another tension that’s arguably even more important.

Performance vs Reliability

Here’s where things get really interesting. Delayed allocation—writing to memory first, allocating disk blocks later—improves performance significantly, but you risk data loss if the system crashes before the data hits disk. Synchronous writes guarantee durability, your data is definitely safe, but they’re painfully slow. Journaling adds some overhead but enables fast recovery after a crash. Copy-on-write never loses your old data, which is fantastic for reliability, but it causes write amplification since you’re always writing to new locations.

Every filesystem picks a point on these spectrums based on what it’s optimizing for.

And then there’s the eternal struggle between doing things the new way and making sure everything still works together.

Compatibility vs Innovation

FAT32’s 4GB file limit and lack of permissions are frustrating, but its universal support is absolutely unmatched—every device on the planet reads FAT32. ext4’s Linux-specific features like extents, delayed allocation, and journaling are great when you’re on Linux, but completely useless if you need to read the drive on Windows. exFAT tries to bridge the gap—it supports larger files than FAT32, it’s simpler than NTFS, and it’s licensed for cross-platform use.

These tradeoffs are exactly why we have so many filesystems to explore. Let me give you a preview of where we’re heading.

What’s Coming in This Series

Now that you understand the foundations, we’re ready to dive into specific filesystems. In each article, I’ll show you exactly how that filesystem organizes data on disk.

We’ll start with FAT32, the universal standard. We’ll see how its beautiful simplicity—just a linked list on disk—conquered the world of removable media. Then we’ll look at ext4, the Linux workhorse, exploring block groups, extent trees, and how it balances compatibility with modern features.

We’ll examine NTFS, Windows’ filesystem, looking at the Master File Table, B-tree directories, and how everything (even metadata) is treated as a file. We’ll explore XFS, the high-performance choice, and see how allocation groups and B-trees everywhere enable massive scalability.

Then we’ll get into the copy-on-write filesystems: Btrfs, the revolutionary filesystem where never modifying data in place enables snapshots, checksums, and self-healing; and ZFS, the enterprise powerhouse with pooled storage, hierarchical checksums, and a reputation as the most reliable filesystem around.

Finally, we’ll look at APFS, Apple’s modern filesystem, and see how it’s optimized for flash storage, encryption, and the Apple ecosystem.

Each filesystem represents different design choices and tradeoffs. By understanding how they work internally, you’ll be much better equipped to choose the right one for your needs—and to troubleshoot when things inevitably go wrong.

But before we dive into all of that, let’s make sure we’ve got the foundations solid.

Summary

Alright, let’s recap what we covered before diving into specific filesystems.

We started at the bottom with storage hardware, which presents a surprisingly simple interface: just a linear array of numbered sectors, typically 512 or 4096 bytes each. The drive doesn’t know or care what’s in those sectors—that’s entirely the filesystem’s problem.

We looked at partitions, which divide a physical disk into logical units, each formatted with its own filesystem. The partition table (either the legacy MBR format or the modern GPT format) describes how the disk is divided up.

Then we explored what filesystems actually do. They provide four essential services: naming (mapping paths like /home/alice/photo.jpg to actual data locations), allocation (tracking and assigning free space), metadata (storing file attributes like size, permissions, and timestamps), and crash recovery (maintaining consistency after power failures or system crashes).

Finally, we looked at the common structures that appear across nearly all filesystems: the superblock or boot sector that serves as the filesystem’s starting point, blocks or clusters as the allocation unit, inodes or directory entries for storing metadata, directories for mapping names to files, and various approaches to tracking free space.

With this foundation in place, you’re ready to see how real filesystems put these concepts into practice. Let’s start with the simplest and most universal one: FAT32.